I wrote a series of articles in 2014-15 for a legal education website. My column profiled some of the many writers and artists who also have a law degree – including Spanish poet, playwright and theatre director Federico Garcia Lorca.

There is, in every law class, the one student who could do almost anything: the passionate polymath; the intense individual with a restless mind and abundant energy; the student blessed with inspiration yet burdened, too, by a strange abiding loneliness.

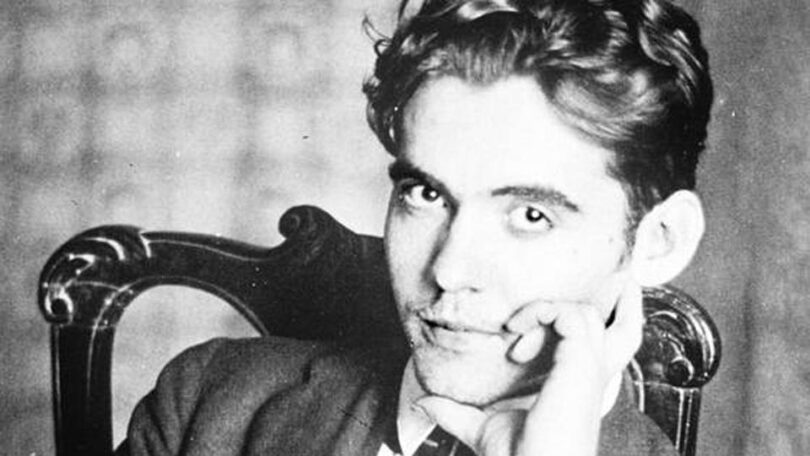

Such was Federico Garcia Lorca, the Spanish poet, playwright and theatre director, born in June 1898 to middle-class parents in a small rural town in southern Spain.

Lorca was 17 when he enrolled to study law, literature and philosophy at Spain’s Sacred Heart University.

He read widely and often, absorbing himself in theatre, music, poetry and art: almost any book or subject unrelated to his degree.

Half-way through law school, Lorca dropped out. Ten years later – without explanation and to the bemusement of his friends – he returned to complete the degree (though he never subsequently practiced law).

In the intervening years, Lorca (pictured) wrote poetry, prose and plays. His first book of poems, published in 1921, explored themes of faith, isolation and nature, and stressed the importance of the natural world.

He published another book of poetry in 1928 that exalted the cultural heritage of the Spanish countryside.

Romancero Gitano (translated as Gypsy Ballads) made Lorca famous across Spain and the Hispanic world, but fame brought him only sorrow.

Success meant recognition and literary expectations, which Lorca strongly resisted. He wrote of feeling trapped.

The gulf between his public persona and private self was a source of intense anguish and despair, a situation exacerbated by the homophobia of the times.

Lorca’s contemporaries and lovers included the Spanish surrealist painter Salvador Dali and the sculptor Emilio Soriano Aladrén.

As Lorca’s reputation increased, he became estranged from Dali. When Aladrén, too, rejected Lorca, the poet’s health and happiness collapsed.

In June 1929, assisted by family and friends, Lorca left Spain for the United States of America to live for nine months in New York and to study English at Columbia University.

He would remember that time as “one of the most useful experiences” of his life – as a period that changed both himself and his art.

He wrote a collection of poems that were published posthumously, in 1942, as Poeta en Nueva York (A poet in New York).

The poems are dark, dramatic, complex and arresting: their imagery confronting; their form experimental, even graphic.

A poet – not Lorca, but some unnamed first-person subject – wanders among the vast, towering sweep of Manhattan, a desperate figure in a sleepless and spiritually bereft city.

The poems condemn urban civilisation but, according to one critic, amount to more than that: they are a “dark cry of metaphysical loneliness…the vigil of modern man in quest of the cosmic meaning of so much suffering.”

Today, this extraordinary collection of poems is widely regarded as one of the most powerful and influential works of 20th-century verse. It is certainly Lorca’s best-known work outside of Spain, and the work that most swiftly elevated his reputation beyond that of a mere gypsy poet.

Lorca returned to Spain in 1930. He was appointed director of a small theatre company and, while touring, wrote some of his (now) best-known plays, all of which rebelled against the norms of bourgeois Spanish society.

He was living and writing with a clear sense of purpose and direction, with real confidence and a potent efficiency. He had fought so hard to find his way; this was his time.

However, the Spain to which Lorca had returned was tearing itself apart in a conflict of radically opposed forces.

In July 1936, when the Spanish Civil War began, Lorca knew that he would be suspect to the rising right-wing for his outspoken liberal views.

“Great art,” he wrote, “depends upon a vivid awareness of death, connection with a nation’s soil, and an acknowledgment of the limitations of reason.”

A month later, aged 38, Lorca was shot and killed by Nationalist Militia, on a roadside in the Spanish countryside. His body has never been found.

That last line might be the saddest last line one could ever read.

And only 38 years old, having just found his way, his voice. Tragic. Sent you a postcard yesterday (should arrive by 2023!). Cheers, Vin! Paul